ON THE night of February 27th 2014, Russian soldiers without insignias—soon to be known as “little green men”—seized the parliament of Crimea. It was the start of Russia’s annexation of Crimea and its war against Ukraine. Exactly a year later, Boris Nemtsov, a leader of Russia’s liberal opposition, was shot dead on a bridge by the walls of the Kremlin. A few days earlier Mr Nemtsov had been handing

out leaflets for a March 1st anti-war rally. The march turned into his memorial procession.

Mr Nemtsov’s postcard murder, with the cupolas of St Basil’s church in the background, marks the return of Russia’s campaign of political violence from Ukraine to the homeland. Russian aggression abroad and repression at home are intimately connected. State propaganda has portrayed Kiev’s Maidan revolution as a “fascist coup” and the democratic Ukrainian government as a Western-backed “junta”, with the Russian-backed rebels in the east of Ukraine as its victims. The media have called on Russian patriots to fight the “fascists” at home, identifying pro-Western liberals as a traitorous “fifth column”, and Mr Nemtsov as one of their leaders.

The anti-Maidan march was the culmination of a long campaign of hatred and intolerance. As Mr Nemtsov said in an interview recorded hours before his death, “Russia is quickly turning into a fascist state. We already have propaganda modelled on Nazi Germany’s. We also have a nucleus of assault brigades, like the [Nazi] SA.” Alexei Navalny, a blogger and opposition leader who was jailed to stop him attending the planned anti-war rally, underlined the emergence of reactionary gangs, “pro-government extremists and terrorist groups which openly declare that their aim is to fight the opposition where the police cannot.”Prompted by the far-fetched fear that the Maidan revolution could be replicated in Russia, the Kremlin has re-imported the violence it deployed in Ukraine. Six days before Mr Nemtsov’s death, the Kremlin organised an “anti-Maidan” protest that drew thousands of marchers to the heart of Moscow, bearing slogans denouncing Ukraine, the West and Russian liberals. Muscle-bound toughs representing Chechnya’s Ramzan Kadyrov, a warlord installed by Mr Putin to keep the territory under his thumb, bore signs proclaiming “Putin and Kadyrov will prevent Maidan in Russia”, alongside photographs of Mr Nemtsov labelled as “the organiser of Maidan”.

Such groups are not grass-roots amateurs who have sprung up on a wave of nationalism, but organisations seeded and financed by the Kremlin. The anti-Maidan activists include the leather-clad “Night Wolves” biker gang, who played an active role in the annexation of Crimea and have been patronised by Mr Putin. More alarming are Mr Kadyrov and his well-trained, heavily armed private militia of 15,000 men, who several months ago swore a public oath to defend Mr Putin. “Tens of thousands of us, who have been through special training, ask the Russian national leader to consider us his voluntary detachment,” said Mr Kadyrov. America and Europe have declared economic war on Russia. Although Russia has regular forces, “there are special tasks which can only be solved by volunteers, and we will solve them.” Mr Kadyrov’s men have long roamed Moscow with arms and special security passes.

This is only the most brazen example of the Russian state outsourcing repression to non-state groups, thus losing its monopoly on violence. Far from being a sign of strength, this is an indication of state weakness. But it is precisely a state’s weakness that often leads it to engage in violent repression. None of Russia’s security experts or former KGB officers believe that the murder of Mr Nemtsov could have been carried out so close to Mr Putin’s office in the Kremlin without the complicity of state security. “It is the territory of the secret service, where every metre is under surveillance,” one former KGB officer explains.

Mr Putin’s initial response was to call the murder a “provocation”. He did not attend Mr Nemtsov’s funeral, although he sent a wreath of flowers. The state media that once hounded Mr Nemtsov began speaking of him in neutral terms. Mr Putin’s propagandists blamed the killing on foreign security services and liberals who wanted a “sacrificial” murder to mobilise their supporters. Ominously, this same scenario was originally floated by Mr Putin three years ago, on the eve of his accession to a third presidential term. The opposition, he said, would sacrifice one of their own and blame the Kremlin.

Many Russian liberals fear that the killing of Mr Nemtsov will be used to unleash a new bout of political repression, as happened in 1934 after the murder of Sergei Kirov, a charismatic Bolshevik leader. Stalin, who is generally believed to have ordered that killing, blamed it on “enemies of the people”. The state information agency, Russia Today, headlined its press conference on Mr Nemtsov’s killing as “Murders of Politicians: the Methods of Maidan”.

Other analysts say a better parallel is not the Kirov murder, but the waves of political killings that swept through Latin American political dictatorships in the 1960s, or Italy in the late 1970s. Such decentralised violence carried out by militant groups in the name of the Kremlin may prove impossible to control. “Even if the Kremlin decides this is enough of hatred, it will be all but impossible to defuse it peacefully,” said Sergei Parkhomenko, a liberal Russian journalist. Given the likely complicity of the Russian security services, few people believe that the assassination will ever be solved. Mr Putin will simply have to cover up for whoever killed Mr Nemtsov.

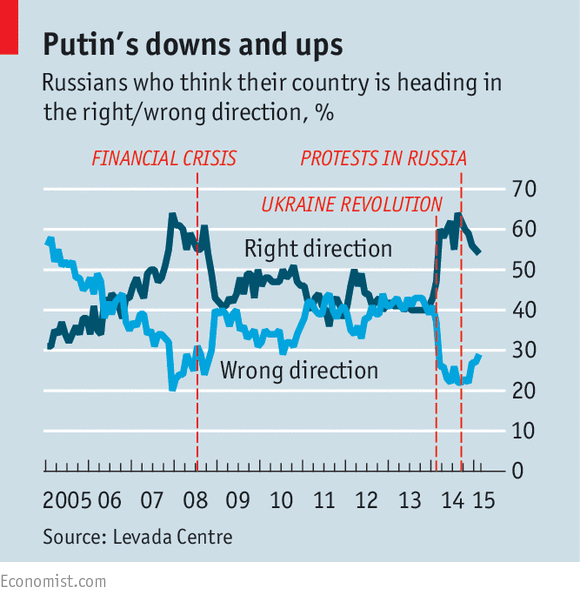

Russian liberals, including Mr Nemtsov himself, had long worried that Mr Putin’s regime would have no choice but to escalate repression and violence as the only way of consolidating its rule. Over the past year, physical violence has been mainly directed against Ukraine. If Mr Putin has now decided that he has reached the limit of his adventurism in that country, he is likely to try to compensate with more repression at home.

The assassination of Mr Nemtsov, who had served in the government of Boris Yeltsin and even been groomed as his potential successor (see

article), has shaken many members of the political elite. It breaks an unwritten pact, agreed after Stalin’s death, that conflicts at the top should be resolved by non-violent means. Those who are still close to the Kremlin and consider themselves liberals now choose their words carefully. Alexei Kudrin, a former finance minister who sponsors civic projects, told TV Rain, a liberal internet-based television channel, that this was a “dramatic page in Russia’s history…in modern, political Russia we see an opponent being stopped by a bullet. This is a new and inadmissible reality and it concerns all of us.” No government officials, including Dmitry Medvedev, the prime minister, spoke out.

Most liberal voices have been drowned in the din of war. The dominant feeling among liberal Russians in the wake of Mr Nemtsov’s murder has been of despondency and emptiness. Grigory Revzin, a columnist, compared the murder of Mr Nemtsov to the killing of Jean Jaurès, a French Socialist leader and pacifist who was assassinated just before the outbreak of the first world war. Mr Nemtsov’s murder, he wrote, was a point of no return.

On March 1st, in place of the planned anti-war rally, tens of thousands of Muscovites marched in complete silence towards the bridge where Mr Nemtsov was killed. The next day, a meeting was held inside the Kremlin. In order to stop the bridge where Mr Nemtsov was killed from turning into a memorial to him, it was decided to use it later this month as the site for a celebration of Russia’s annexation of Crimea.