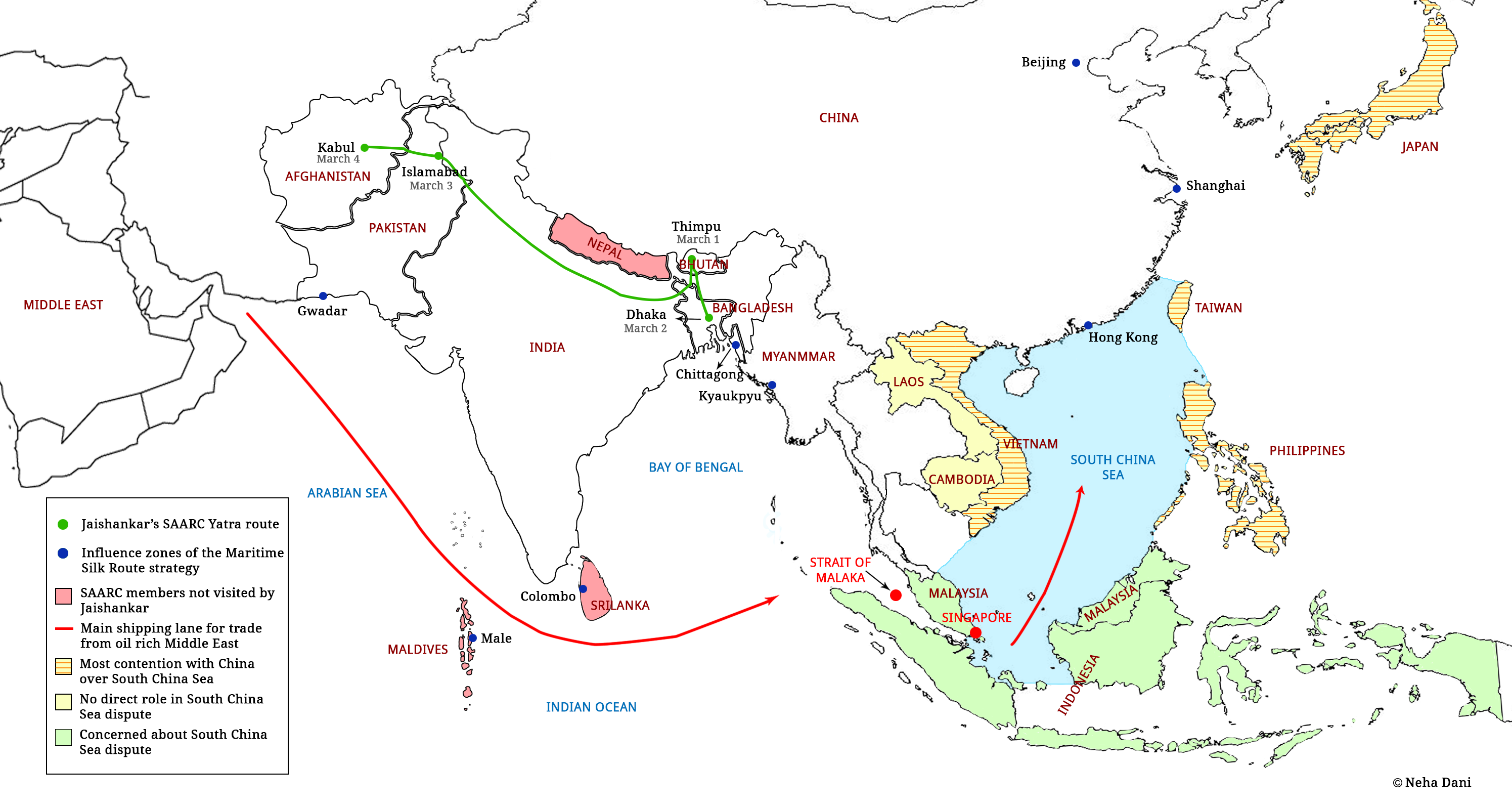

Indian Foreign Secretary S Jaishankar recently took a whirlwind tour of parts of South Asia, visiting Bhutan, Bangladesh, Pakistan and Afghanistan over four days. Described as the first phase of his “SAARC Yatra”, the trip was undertaken to strengthen India’s relations with its neighbours. Though all parts of the journey got noticed, it was predictably Jaishankar’s stopover in Islamabad that got the most attention. After a six-month-long freeze in direct talks, the visit was seen as an ice-breaker: Jaishankar met his Pakistani counterpart Aizaz Ahmed Chaudhry and Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, and both sides decided to “narrow differences”.

While Nepal, Maldives and Sri Lanka were missing from the itinerary, the tour was still seen by many pundits as a key event extending Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s vision of frequent bilateral exchanges with India’s neighbours. In their focus on the India-Pakistan dynamic they took little notice of the fact that India’s strategy for its neighbourhood has long turned southwards, towards a region that is much-contested now but was earlier taken for granted as New Delhi’s sphere of influence: the Indian Ocean Region.

China, as is known, has been working to dominate this region. Its plans for a Maritime Silk Route – starting from Mainland China, passing through the contested South China Sea, and then the Indian Ocean to Africa and West Asia – is seen as a strategic threat by India. Besides, it has made forays, or is making them, into all three waterfronts of India – the Indian Ocean, Bay of Bengal and Arabian Sea.

In the Arabian Sea, it has established presence by constructing and operating the port city of Gwadar in Pakistan. The oil will be transported and stored at Kyaukypu and then transported into mainland China using pipelines.

After making large investments in Sri Lanka, Myanmar and Pakistan, China is looking to expand its presence in Bangladesh, and the strategically important island nations of Maldives, Mauritius and Seychelles in the Indian Ocean Region. It has shown interest in funding the development of Chittagong in Bangladesh as a potential trade hub, and has signed a deal to supply Dhaka two Ming-class submarines. All these developments have given rise to the fear that Chinese warships may dock at Chittagong in the future.

New Delhi has recognised the challenge offered by China in the Indian Ocean Region, and its response is visible. A strategic rethink in India’s defence and strategic policy for the Bay of Bengal is underway, and the Indian Ocean now commands more Indian diplomatic capital than ever before.

Click here

Click here to expand image.

The first revealing challenge to India’s sphere of influence in the Indian Ocean had emerged in 2012 in Maldives, when the country “short-changed” Indian company GMR’s airport project there. Tests have kept coming since then.

The recent political upheaval in Maldives’s capital Male, with former President Mohamed Nasheed being dragged to court, as he complained of being denied proper legal representation, raised eyebrows in New Delhi. Though India raised concerns with current President Abdulla Yameen’s regime, reminding it of the rising radicalism in that country, the Maldivian government maintained a defiant face. It instead highlighted its regret that China had kept quiet on the issue (or, in other words, not backed it).

Beginning March 10, Prime Minister Modi is slated to tour Sri Lanka, Mauritius and Seychelles. Maldives, which was earlier reported to be on Modi’s itinerary, has fallen off it after the Nausheed episode. While some sources suggest Modi’s visit to Male remains undecided, others say this may be a way of sending a message to the Maldivian government, and that Jaishankar will visit Male after Modi's “Hind Mahasagar Yatra” is over.

Whatever the changes to Modi’s itinerary, the hectic diplomatic moves by South Block in the Indian Ocean Region will continue. As will astute manoeuvrings by Beijing in the region. China recently announced a 10% increase in its annual defence budget, taking it to more than $140 billion (India’s is around $40 billion). Much of this new infusion is reportedly meant for the Chinese People's Liberation Army Navy, which in turn would mean more muscle for China in the Indian Ocean Region and more worries for India in its neighbourhood.