After a tumultuous 13-year journey, the Rajya Sabha finally approved the constitutional amendments that will enable the Goods and Service Tax (GST) to become a reality. Without question, the coming together of all parties was a commendable effort and the Indian GST will be the largest tax reform to be implemented anywhere in the world. The media and business leaders are euphoric, labelling this a “one nation, one tax” measure that will boost the GDP and usher in a new era of economic prosperity by significantly improving ease of doing business. One commentator even claimed that GST would “almost eliminate corruption”.

In reality, the constitutional amendment is just the first step and does nothing more than enable the Centre and the states to implement a new method of taxation — GST. The herculean task that lies ahead is the implementation of this gigantic tax reform which will require the successful tackling of several issues.

India’s GST will be the world’s most complex version of a GST or VAT. In most countries, GST means one tax for all commodities and services and is applied throughout the nation. Article 246A enables parliament and states to concurrently levy GST. Service tax, which is a central levy, will now also be levied by states and comprise part of the GST. The net result is that we will have 31 GST enactments (for 29 states and the union territories of Puducherry and Delhi). Therefore, “one nation, one tax” will really be “one state-one GST”. This is apart from separate enactments of Central GST (CGST) and Intra-State GST (IGST). Besides GST, the states will continue to have the power to levy sales tax/VAT on petrol, diesel, aviation fuel and potable alcohol. The Centre can continue to levy excise duty on all these products as well as on tobacco and tobacco products. Whatever the merits of the Indian GST, simplicity is not one of them.

It is critical that all states follow one model enactment; the greater the deviation, the greater the headache for industry. The present constitutional amendment gives only recommendatory powers to the GST council. Nothing curbs a state that decides to strike a deviant path.

The heart of any GST system is a single rate of tax applicable to all commodities and services. It is better to have one lower rate for all commodities than to have multiple rates for different products. We have opted for the latter and multiple rates are expected: zero rate for essential commodities, 2-4 per cent for gold jewellery, 12 per cent for “merit items”, 18 per cent or more as the standard rate and 40 percent for luxury products. Under Article 279A(4), the GST council can also recommend limits for granting exemptions, “floor rates with bands of GST”, special rate for specified periods to meet natural calamities/disasters, and special provisions for the north-eastern states, Jammu &

Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand. These multiple rates will get further complicated if different states start granting different exemptions. And with each state having plenary power under Article 246A, what happens if some states begin to levy an additional tax or a surcharge? Indeed, even if the GST council recommends a rate of 18 per cent, there is nothing to prevent a state from increasing it to 22 per cent or even reducing it to 12 per cent. If other states are affected by such an increase or decrease, do they approach the GST council? Is any state’s right to approach the supreme court under Article 131 taken away? To what extent is the decision of the GST council binding? These are just some of the questions that require serious contemplation.

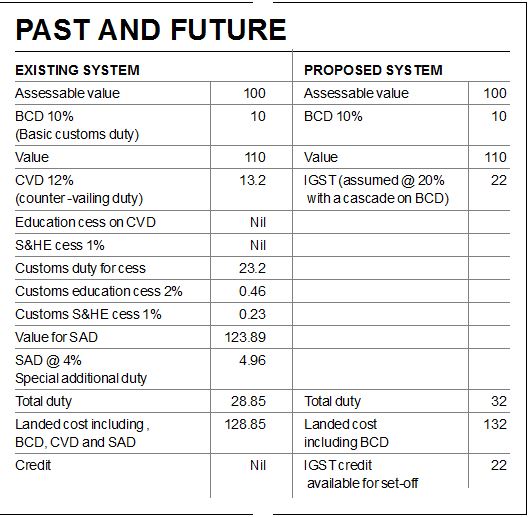

Another dangerous consequence of the GST regime is that imports will be cheaper as the IGST on imports will be entitled to a set-off against the final selling price. This is not permissible under the existing regime, as the table indicates. Thus, imported goods will now be cheaper because the IGST at Rs 22 can be off-set by the importer when he sells the goods in the domestic market. The net cost to him will be Rs110 as against Rs128.85 in the earlier regime. Undoubtedly, the GST regime will bring down manufacturing costs by reducing the cascading effect of indirect taxes and through improvement of supply-chain efficiencies. But these benefits must be mathematically greater than the benefit that will accrue to direct imports. With highly cumbersome labour, tax and regulatory laws in most states, manufacturing is hardly a happy activity. If imports become even cheaper, the Make in India campaign will be adversely affected.

There is considerable uncertainty over the actual manner of implementation of the GST regime. With the overlapping of taxes, how will the multiple laws be administered? Since the GST is a separate concurrent levy by the Centre and the states, how will the disputes be resolved? Will each state have its own GST tribunal? The model law is unduly harsh in several respects. For example, GST credit will be available only if the buyer of goods furnishes proof that the vendor has paid GST to the government account. Therefore, a lawyer or businessman cannot claim GST credit on the GST paid on his laptop unless he can prove that the seller has paid GST to the government.

Extremely serious issues need to be resolved on e-commerce transactions, dual taxation and restricted credit. Each State will not only have its own GST but each act will have multiple rules. With CGST and IGST, there are bound to be separate credit pools for SGST, CGST and IGST. Preliminary studies show that there will be a substantial increase in paperwork and compliance costs.

With these multiple problems likely to arise in the immediate future, it is best that the GST is implemented in stages. When the Modvat Scheme was introduced in 1987, it was first applied to only 37 commodities and then expanded to other products. It is best to implement GST on a trial basis in a few manufacturing, trading and service sectors. This will reveal possible hurdles that require attention and will also help in perfecting the IT infrastructure that is so critical to a successful GST. Above all, GST will require states to eschew short-term thinking. With several states indulging in disastrous populist schemes, this will require statesmanship of a very high order. As Henry Ford put it: “Coming together is a beginning; Keeping together is progress.”