As the year 2018 was drawing to a close, the Union Cabinet quietly cleared the Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) Notification, highly debated upon for its impact on coastal ecology. Before it was made public, swarms of real estate agents had started visiting the shanties of South Mumbai where the country’s commercial capital tapers into the Arabian Sea. Valli Sengena, a rag picker from Sundar Nagari is highly sought after by the developers and their agents. Every day, as they visit the colony to cajole hundreds of fisherfolk, cleaners and domestic helps to obtain their written consent for acquiring the land, Sengena helps them make a deal. “I’ll sell my jhuggi only when I get a lucrative offer. It is located bang on the coast and offers a beautiful view of the Gateway of India,” Sengena says.

A few kilometres away, decades-old housing societies have begun holding urgent general body meetings to redevelop the property for more floor area. At places, developers are also eyeing the mangrove forests to set up tourism facilities. “The notification allows taller buildings in developed areas and construction along the shoreline,” explains reality consultant Tarun Chandiramani. But such activities will spell doom for a region like South Mumbai, which is vulnerable to erosion, cyclones and storms. Denser construction will further heighten its vulnerability.

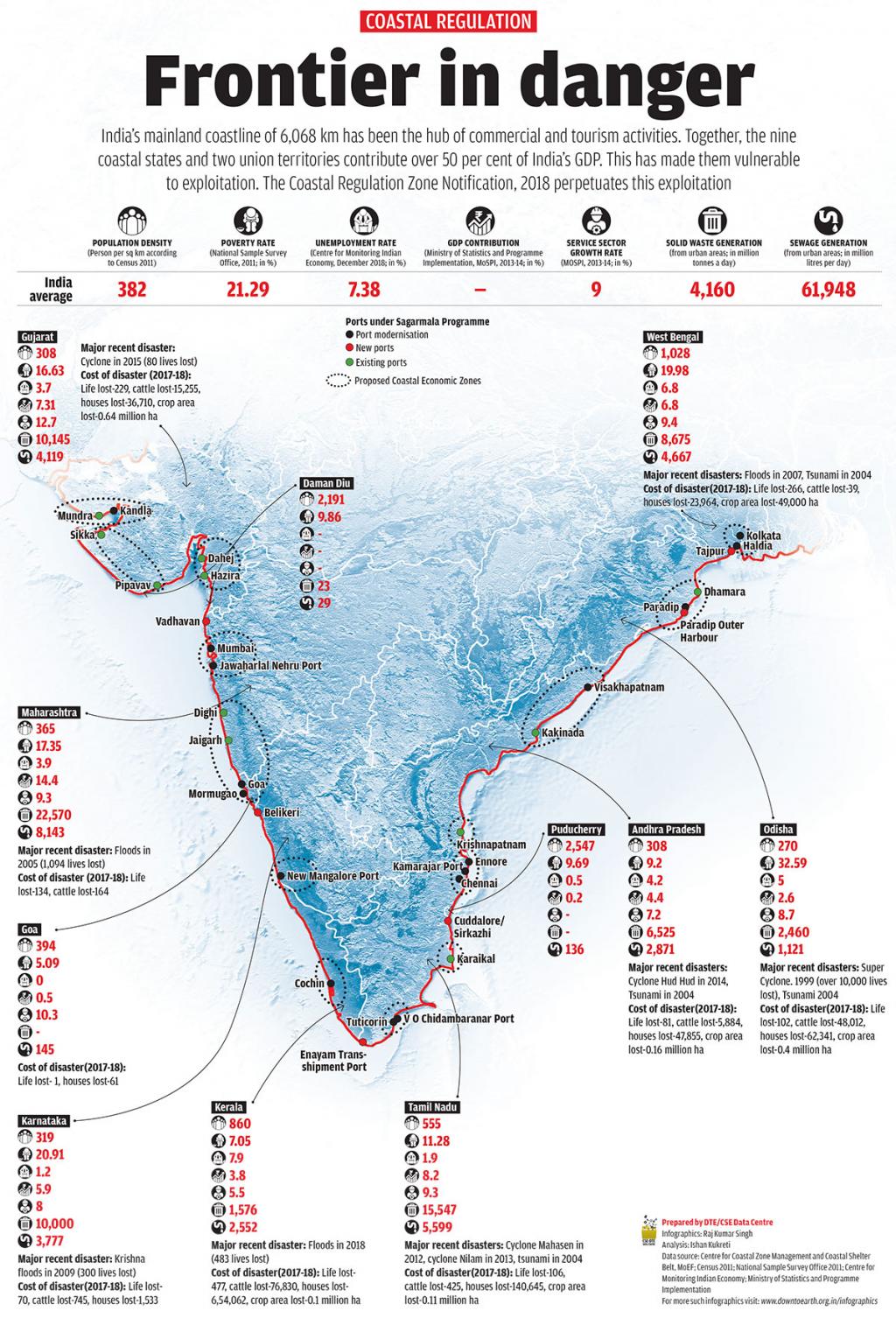

The government statement is clear: “The proposed CRZ notification 2018 will lead to enhanced activities in the coastal regions thereby promoting economic growth while also respecting the conservation principles of coastal regions. It will not only result in significant employment generation but also a better life and add value to the economy of India.” But environmentalists say the notification favours limited interests. By opening up 6,068 kilometres (km) mainland coastline for more commercial activities, it has put at risk the ecology and communities vulnerable to extreme weather events and sea level rise.

Regularising population and commercial pressure on the active play zone of the sea waves was at the heart of the notification, when it was first issued in 1991 under the Environmental Protection Act, 1986. It demarcated an area up to 500 metres from the high tide line (HTL) all along the coast as CRZ, classified it into four categories depending on their land use or sensitivity and regulated developmental activities in the areas. In the aftermath of the 2004 tsunami, which killed 10,000 people along the eastern coast, CRZ Notification 2011 was brought in to beef up coastal zone. But over the period, CRZ has been more violated than protected.

In fact, over the last 27 years, the notification has been iterated twice and modified 34 times, making it the most amended law in the history of India.

“The objective of the latest notification is fundamentally different from the earlier ones,” says Kanchi Kohli of the Centre for Policy Research, a Delhi-based think-tank.

For instance, as per the 2011 notification CRZ-1 includes the most ecologically sensitive areas like mangroves, coral reefs and sand dunes, and intertidal zones. It was off-limits for tourism activities and infrastructure development, except for defence, strategic and rare public utility projects. The latest notification further categorises CRZ-1. It allows “eco-tourism activities such as mangrove walks, tree huts, nature trails, etc” in eco-sensitive areas, demarcated as CRZ-IA. Sea links, salt harvesting and desalination plants and roads on stilts are also allowed in CRZ-IA. The controversial land reclamation, in which new land is created from oceans or lake beds and is known to have strong impacts on coastal ecology, has been allowed in intertidal or CRZ-IB areas, for ports and sea links.

In CRZ-II, a substantially built-up area, project developers can now increase the floor area ratio or floor space index, and build resorts and other tourism facilities. A large part of South Mumbai falls in this category.

Under earlier notifications, hotels and beach resorts were also allowed in CRZ-III, or relatively undisturbed areas that do not fall under CRZ-I or II. But their construction was prohibited in no development zone (NDZ) of CRZ-III, which extends landwards up to 200 m from HTL. The latest notification drastically shrinks NDZ to 50 m from HDL in densely populated areas (where population exceeds 2,161 per sq km as per the 2011 Census). This technically allows resorts, hotels and tourism facilities to be built right up to HTL.

“Providing housing facilities just 50 m from the coastline would expose the inhabitants to severe weather events, that too without any buffer,” says V Vivekanandan of Fisheries Management Resource Centre, a non-profit in Chennai.

CRZ-IV, which includes the shallow belt of coastal waters extending up to 12 nautical miles, is not only a crucial fishing zone for small fishers but also bears the maximum brunt of waste from offshore activities, such as oil exploration, mining and shipping. The 2011 notification had thus laid importance on regulation of pollution from such offshore activities. Instead of strengthening the regulation, the 2018 notification allows land reclamation for setting up ports, harbours and roads; facilities for discharging treated effluents; transfer of hazardous substances; and construction of memorials or monuments.

What’s distressing is no study is available to show the carrying capacity of coastal areas to accommodate such increased development or the projected impact of such a change on the coastal communities.

Rights wronged

CRZ 2018 overrules the concerns of 171 million, or 14% of the population living in coastal districts. Over 12 million of them depend on fishing

Back in 1991, the safety and livelihood of the coastal communities was given priority while drafting CRZ notification. “In fact, the committee under MS Swaminathan, set up in the aftermath of the tsunami, went as far as suggesting a land rights recognition law along the lines of the Forest Rights Act, 2006 for the communities who subsist on the coastal areas based on their customary rights,” says Vivekanandan.

The suggestion was never implemented, and now the precarious nature of their customary ownership makes them easily dispensable to make way for tourism and other development, he adds.

Contrary to the 2011 notification, which clearly says fishing activity by communities will not be regulated, the new notification puts them under the regulated category. “CRZ-III areas are the ones where traditional communities live and subsist on the natural resources. While the notification changed the land use in CRZ-III areas to bring in tourism, its impact on the livelihood of local communities have not been taken into account,” says Kohli. According to T Peter, general secretary of National Fish Workers Forum and member of the Kerala Independent Fish Workers Federation, the new notification brings clearance in CRZ-IV areas under the purview of the Centre. “Earlier, the area was under state government. Now with the Centre giving clearances for projects in the area, it will be difficult for communities to get their voices heard in Delhi,” Peter says.

This indicates serious flaws in the drafting process. “Coastal ecology is volatile, with changing coastline. So, most activities by the traditional communities in these areas are seasonal in nature,” says Kohli. Yet, the government has relied on satellite imagery to demarcate CRZ categories with little or no corroboration on the ground. This will lead to increase in conflicts in the future,” she says.

While these conflicts could have been avoided by holding consultations with communities, it was done in frivolous manner,” says Probir Banerjee of PondyCAN, a non-profit working towards costal restoration. “I attended a meeting in Puducherry. It barely lasted an hour and people did not really know what was at stake,” he adds. While the drafting of 2011 notification is known for holding 11 consultations with stakeholders, from companies to communities, the Sailesh Nayak committee, responsible for the latest 2018 notification, was more of a closed door discussion among bureaucrats.

Even the committee report was not put in the pubic domain, until a Right to Information application was filed.

Industry lobby at WORKS?

550 ports and related projects, 14 economic zones, 11 tourism circuits, roads stretching 2,000 km under way along the coastline

The notification comes at a time when India’s coastal zone is teeming with activities. The most ambitious of all is the Sagarmala programme. Launched in 2015 by the Ministry of Shipping, it “aims to promote port-led development” by harnessing the “7,500 km long coastline (including offshore islands governed under Island Protection Zone Notification since 2011), 14,500 km of potentially navigable waterways and strategic location on key international maritime trade routes”. The government has identified about 550 projects worth Rs 8 lakh crore to be implemented by 2035. So far, 14 have been completed and 69 are under construction.

To boost industrial and exports growth, Sagarmala also envisages setting up 14 coastal economic zones (CEZs), each housing a industrial clusters, ranging from petrochemical, cement, leather to power, electronics and food processing. Coastal and port connectivity roads, stretching 2,000 km, under the Bharatmala project of road and national highways are also being planned.

Experts say the notification has been drafted to facilitate these flagship projects of the government. For instance, its provisions for land reclamation and permission to build roads even in ecologically sensitive CRZ-I facilitates the creation of CEZs. The government has declared Sagarmala, Bharatmala and CEZs as “strategic projects”, which have blanket exemption from CRZ provisions. The sea, tidal wetlands, virtually any kind of geography can be legally obliterated for such projects. “While land reclamation was being done surreptitiously earlier too, CRZ 2018 notification gives a clear indication for land reclamation,” says Kohli.

Initial experience shows ports under Sagarmala are causing ecological devastation, barely benefitting the communities.

In Valiyathura, a fishing village in Kerala’s Thiruvananthapuram district, the sea gobbled up over 200 houses between June and July 2018 (photo above). Part of the office of the Valiyathura branch of the National Centre of Earth Science Studies has almost been levelled by the coastal erosion, says Sheeba Patrick, ward councillor of the area. Residents blame it on the Vizhinjam Port, built by multinational conglomerate Adani as part of Sagarmala. “At least 15 kilometres of the coast and 30,000 people will be affected when Vizhinjam project is completed,” says Joseph Vijayan, who has been fighting for over four decades to protect the livelihood of fisherfolk in Kerala.

The fishing community in West Bengal’s port city of Haldia narrates a similar tale. Eight jetties are being planned under Sagarmala in the river port. “Effluents from the Mitsubishi Chemical Corporation Plant has already poisoned the Hooghly river.

Our income from fishing has reduced by one-third since industrialisation started in the region two decades ago,” says Saibul Ali, a fisherman at Rupnarayan bank in Haldia. “Once the jetties are in place, fish will stop coming to the shore.

Finding a place to cast the nets will be a task because of ship movements,” says Angshuman Midya, president of Rupnarayan Chawk Matshya Obotaran Kendra, a fishers’ cooperative.

Though development of coastal communities is one of the four pillars of Sagarmala, so far, Rs 1,415 crore has been allocated towards communities against a massive outlay of Rs 3,91,987 crore towards port modernisation and new port development; port connectivity enhancement and port-led industrialisation. Explaining the futility of the programme, Debi Goenka, executive trustee, Conservation Action Trust, says, Indian ports are neither on the major international shipping routes nor do they have the capacity to handle large ships. Why would they come to Indian ports? Data available with the Ministry of Shipping shows that while the capacity of major ports was increased from 965 million tonnes per annum (MTPA) to 1,451 MTPA between 2015-16 and 2017-18, their capacity utilisation has plummeted to 46 from 62 per cent during the period.

At other places, the Ministry of Tourism’s Swadesh Darshan Scheme is at loggerheads with fishers. Under the scheme, 11 theme-based tourist circuits, are being built in seven coastal states, the Andaman and Nicobar islands and Puducherry. One such circuit is in the making at Chennai’s Marina and Elliot’s beaches at the cost of Rs 14.60 crore. The authorities plan to provide Wi-Fi facility, sea-view seating, first-aid kiosks and e-toilets to tourists visiting the beach and better connectivity to reach the place. So they have converted a service road on the Marina beach into a high-speed concrete road. It has been traditionally used by people from Nochikuppam slum for selling fish and emptying and mending their nets.

In times of CLIMATE CHANGE

In the past two decades, 45% of coast has been lost due to erosion; natural disasters along the coast has cost the country $80 billion

From severe cyclonic storm Ockhi and the freak monsoon in Kerala to the devastating cyclone Gaja, the sea remains a harbinger of bad news for India. In October 2018, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released a report warning that global temperatures have already risen by 1.2°C; mean rate of sea level has risen by 1.7 millimetres a year between 1901 and 2010, resulting in a rise of 0.19 metres. Studies by the Indian National Centre for Ocean Information Services, say the sea level along India is rising at 0.33-5.16 mm per year and predict that the frequency and intensity of unseasonal and extreme weather events will increase in the coming decades. According to a study by the UN International Strategy for Disaster Reduction, natural disasters along the Indian coast cost the country $80 billion between 1998 and 2017.

Worse, according to the Central Water Commission’s Shoreline Change Atlas, India has lost 3,829 km, or 45 per cent of the coastline, in just 17 years till 2006. While coastal erosion is a natural phenomenon carried out by waves, tidal and littoral currents and deflation, the report says these factors get exacerbated by activities like land reclamation, dredging of harbours, navigational channels and tidal inlets, construction of groynes, jetties and other structures on the coast.

The National Centre for Coastal Research under the Ministry of Earth Sciences, in its Status Report Seawater Quality Monitoring (1990-2015) found pollution levels rising in coastal waters. It found ammonia and phosphate levels to be high in all the 24 locations that were monitored, which it attributes to dumping of untreated sewage into the ocean. “Increasing nutrients in the coastal water may lead to ecological disturbances affecting the coastal ecosystem processes and services,” the report warns.

CRZ notifications right from 1991 have stressed on planned phase out of untreated sewage and waste disposal in the water. But this provision is rarely implemented despite the fact that all states, barring Goa and Kerala, have their Coastal Zone Management Plans in place.

Under these circumstances, it is imperative to bring in a stringent coastal policy, to conserve both the ecology and the communities. “The government, instead of releasing notification after notification and introducing infinite number of amendments, should come up with a comprehensive act for the coastal areas,” says Peter.

Banerjee says the best way to protect the coastal zone has probably been answered in the European Commission’s 2004 study, “Living with coastal erosion in Europe”. It says just leave the beach intact!

(With inputs from Gajanan Khergamker in Mumbai, Sudarshana Chakraborty in Haldia and Rejimon Kuttappan in Thiruvananthapuram))